I needed to restock my storecupboard this weekend, so we headed for Oriental City (see my earlier post on Oriental City’s food court for directions). It’s probably my favourite source for exotic ingredients, as the supermarket extends to cover Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Malaysian and Thai ingredients alongside the Chinese bits and bobs you’ll find in many other oriental supermarkets, and has a remarkably good selection of fresh produce flown directly from Asia.

They’re currently reorganising the supermarket to extend the Japanese section, which has a grand re-opening later in August. All of the shelves are clearly labelled in English so those with problems reading Japanese, Chinese, Thai and Korean orthography do not accidentally buy tinned silk worms (something I have still not been able to bring myself to sample). The supermarket is also an absolute joy for fresh ingredients; the pictures below are just a small selection of the fresh goods on offer.

Six different kinds of chilli. There were more on another shelf, and a further shelf of dried chillis further back in the supermarket.

Turmeric, young ginger, galangal and other juicy, fresh roots for pounding into pastes.

Six different kinds of small aubergine. I used the purple ones towards the right in a Thai green chicken curry yesterday.

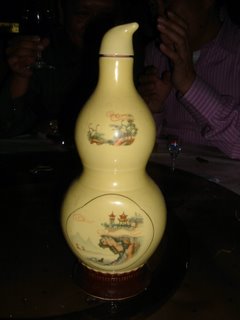

The fresh fruits, spices and vegetables extend all the way down one wall. You’ll find Asiatic pennywort, pandang leaves, banana leaves, lily buds, gourds, mooli, a million and one variations on the theme of a cucumber, perilla, lotus roots, herbs like Mitsuba…it’s a challenge to recognise everything.

While many places will only stock one kind of soya sauce or one kind of fish sauce, this supermarket prides itself on the choice it offers. I counted six kinds of fish sauce, and one side of an entire aisle is given over to different soya sauces. The chilli sauce aisle is packed tightly on both sides with bottle upon bottle of the red stuff, and there were seven different brands of instant dashi, alongside the bonito flakes and kelp you need to make your own.

Ex-pats craving snacks from home are well catered for. These Japanese snacks are on offer at the moment so they’re out of the way before the advent of the new Japanese section, which will, apparently, carry even more.

Here’s that crab again, with some other fish so you can get an idea of scale. The fish counter is one of the fewI’ve found that will actually carry fresh, properly prepared fish specifically for making sushi and sashimi at home. (It’s also a good place to find roes like tobiko and a fresh salmon roe.) Cuts of meat which aren’t usually represented in UK butchers are also easy to find here; chicken’s feet come frozen or fresh, and there are even duck tongues for the brave.

If you live in or near London, or if you’re just passing through, try to pay a visit to Edgware and see what you can find at the supermarket. Cook with something you’ve never tried before. Try to find out which is the strongest chilli. Use those canned silkworm larvae to broaden your experience. I’d love to find out how it goes.