Regular readers of Gastronomy Domine will be aware of my vintage cookery book habit. I’m hoping to make something of a semi-regular feature of posts about some of these books; if you’ve an interest in food and in social history, an elderly cookery book is a goldmine. Cookery for Invalids, written in 1900 (mine is a later edition), is a book of “recipes and diet hints for the sick room”, and will make you gladder than you’ve ever been that you live in an age of antibiotics, insulin and ubiquitous refrigeration.

Regular readers of Gastronomy Domine will be aware of my vintage cookery book habit. I’m hoping to make something of a semi-regular feature of posts about some of these books; if you’ve an interest in food and in social history, an elderly cookery book is a goldmine. Cookery for Invalids, written in 1900 (mine is a later edition), is a book of “recipes and diet hints for the sick room”, and will make you gladder than you’ve ever been that you live in an age of antibiotics, insulin and ubiquitous refrigeration.

Senn, born in 1862, was a chef and a prolific writer of food books, producing 49 books in his lifetime – a remarkable feat given the limited scope of the Victorian and Edwardian kitchen in England. (He had an eye for a new angle; I would love to get my hands on a copy of his Cooking in Paper Bags and Ye Art of Cookery in Ye Olden Time.) By far his most successful book was Cookery for Invalids, first published in 1900, which ran to many editions and seems to have been published at least until the 1930s. (Penicillin was finally purified and tested on humans in 1941, and, of course, many presses closed for the Second World War – I haven’t seen any evidence of printings of the book in the 40s.) Senn himself practised as an early nutritionist as well as a chef, working as Examiner in Sick-Room Cookery at several London hospitals; he was also employed by the government to set up training for army, navy and prison cooks. This was a time when nurse training at the larger hospitals included short courses in what was termed Invalid Cookery, to be practised on their convalescent charges. A wealthy family would employ a children’s nurse for their perfectly well offspring. While dandling, disciplining and doing a bit of mild educating, she was also expected to produce nutritious and stimulating meals for the children; training in dietetics was considered a great boon in such a nurse.

Diet was recognised as a contributing factor in illnesses like diabetes and gout, and was believed to be an efficient treatment in illnesses like neurasthenia (a disease we don’t recognise any more – it was that which affected swooning ladies in the drawing room) and rheumatism. There was a vogue for nutrition, and a huge industry in patent foods like Benger’s (a nourishing wheat and milk preparation); we still recognise plenty today, like Horlick’s, Bovril and Lucozade.

Cookery for Invalids contains a brief explanation of the make-up of foods: protein, carbohydrates, fat, salts (what we would describe as minerals), vitamins and water; a discussion of the suitability of various styles of cooking for the sick (horrible imprecations on those preparing fried food here); a series of recipes; and a list of special diets for those suffering various named, and usually pretty horrible, illnesses. Some of this stuff is curiously modern. I was particularly surprised to see that the daily calorie intake dictated by Senn is, at 2500 kCal, exactly the same as that the NHS tells us to keep today in 2010 – although admittedly, Senn’s patient doing “hard work”, when a lot of what is done today with machinery was still done by people, was allowed to increase his daily intake to between 4000 and 9000 kCal. Writing a good 70 years before Dr “Fatty Fatkins” Atkins, Senn suggested that carbohydrates were the most important part of the diet to cut out in slimmers. His approach to the sick is compassionate, kind, and non-patronising; the pretty tray on the book cover (above) is illustrative of his insistence throughout the book that food should “please the eye as well as the palate”; lack of appetite is a hurdle in most of the illnesses being treated. “The patient’s wants should be studied, and their wishes gratified as far as possible…in feeding a patient do it gently and neatly.” Cleanliness is paramount. NHS hospitals could learn a thing or two.

The Edwardian invalid’s lot was not, all that said, a happy one. While the awful drinks made from burned toast soaked in warm water that you see in the sickroom sections of Victorian cookery books don’t get a look-in here, the Edwardian convalescent was still expected to be bibbing heartily at mug upon mug of beef tea; it was thought to be easy to digest and full of delicious nourishment while “preventing the digestive organs from doing undue work”. As such, Senn recommended it for all patients.

The method is shudder-inducing. The nurse would shred a chunk of lean beef with a couple of forks, discarding gristle and fat, and soak the resulting beef tartare in a big jar of cold water for an hour or so before straining the resulting mush through muslin “with a tiny pinch of salt added”. Lucky invalids might have their beef tea warmed through. “Beef tea must never boil. If it approaches boiling point it is spoilt.” There are eight recipes for beef tea (slow method, raw method, quick process, iced, jellied and so on) here. Variety may not be the spice of life after all. Spice, in fact, was out of the question – far too stimulating. “Stimulants are in many cases positively harmful…spices should be avoided, and where pepper is allowed it must be used sparingly.” Wine, however, might be allowed with the doctor’s permission; “it often tempts the appetite…when other and more solid food would fail”.

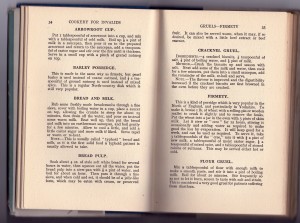

Gruels were easy to digest, and this archetypical invalid dish is given its own section. Click on the picture to enlarge this page of gruel recipes to a readable size – besides what you can see here, there are several more pages of gruels, one of which has a wine-glass of sherry poured into it. Thoughts of Oliver Twist aside, sherry gruel sounds abominable. When you’re done with your gruel, “A raw egg beaten up and mixed with a cup of milk, tea or coffee, makes an excellent and nourishing drink.” I shall refrain from comment.

It’s not all so bad. There are palatable and light fish and chicken preparations, a nice little quail on toast, and a herby poached rabbit in Bechamel; unfortunately, there’s also a sandwich filled with raw mutton and sugar, and a custard made with Marmite. I can imagine the patients of owners of this book conniving to die early just to get away from the cooking.

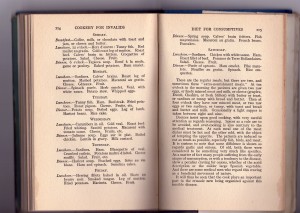

So far, so frivolous. But all your sniggering postmodernity counts for nothing once you get to the final part of the book, which discusses specific illnesses. By the time Senn was writing, the control of type II diabetes through diet (as we do today) was well understood. His diabetic menu would stand up to scrutiny today; and saccharine, discovered in 1878 and commercialised very shortly afterwards, was a real blessing for the Edwardian diabetic. The diet for gout is also similar to what a doctor might suggest today, and the “reducing” diet for the obese is dull but looks effective. But what we will understand as the futility of trying to cure tuberculosis in the pre-antibiotic period through diet, fresh air and rest, is heartbreaking. The week’s menu for the consumptive here on the right (again, click to enlarge) is, as long as you were able to stomach calves’ brains three times a week, pretty palatable, but entirely useless for curing the patient. The massive weight loss that was one of the outward signs of the disease is all the diet tries to address; an earlier page on TB clings to the ancient superstition that red fluids like wine were good for replacing the blood coughed up, along with minced raw meat.

I’ll leave you with some of the advertisements from the front and back of the book – judging by the prices on the products and the graphical style of these ads, I think this edition is from the 1930s. You may recognise some of the products here – you can still buy Shippam’s meat and fish pastes (I used to love the fish paste in my school sandwiches), Borwick’s baking powder and McDougall’s flour. God only knows what became of the Stuffo stuffing company, and you won’t see isinglass outside the brewing process these days; it would have added a distinctly fishy tinge to your jellies, but was much cheaper than gelatine.

An earlier edition of the book (there are very few differences – the most notable one is probably the substitution of the word “corpulency” in the older text with “obesity” in the one I own) has been digitised and can be read online here. If you decide to try any of the recipes from the book, do drop me an email or leave a comment – especially if you tried any of them out on ill people. I’ll be interested to hear whether they ever recovered.