“…And we got to spend an afternoon with Darina Allen at Ballymaloe,” I said to some Irish friends back here in the UK, on my return from our bloggers’ pootle around the foodier bits of Cork and Waterford. Frequently, Irish eyes are held to be smiling. On this occasion, they all rolled back in their respective skulls with envy.

“Darina Allen? She’s the only person whose recipes I use! Em…apart from yours, of course, so,” said one friend, upon which she immediately started fiddling with her beer. “You are so lucky,” said another. “I would kill to spend an afternoon with Darina Allen.”

Her husband (English), shuffled away from her nervously on his bottom. “Who’s Darina Allen?”

This comes under the class of questions that you should never ask an Irish person if you do not wish to be scoffed at vigorously. “You know your woman Delia Smith? Like that, but good. And organic. And without the football and the shite food,” said one angry Irishwoman. “She is only the whole reason that Irish food is any good these days. And you know that pot-roast you like? And the raspberry roulade? And all the stuff from that big white book in the kitchen? I can’t believe you don’t know who she is.”

“Jaysus,” agreed Irish friend #1.

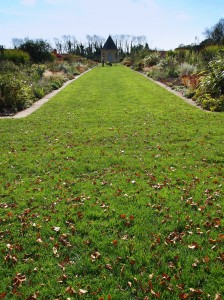

Darina is, in fact, the dynamic force behind the world-renowned Ballymaloe cookery school, set in the middle of its own 100-acre organic farm and gardens. She’s head of the country’s slow food movement, is currently very deeply involved in a project to get farmers’ markets embedded in Irish shopping culture, is the author of a vast number of cookery books, and, alongside teaching at the cookery school, works as a TV presenter and newspaper columnist. She might well be the most energetic person I have ever met – our meeting at Midleton farmers’ market resulted in an impromptu whistlestop tour of the market, followed by sublime pizzas at the Ballymaloe cookery school’s Saturday Pizza Kitchen (a business idea totally out of left-field but typically popular and successful), and a long tour of the gardens and farm. At all stages in the day, Darina was multitasking. Collecting firewood as we walked around the gardens; shouting encouragement and advice to gardening staff; swiping invisible motes of dust off pristine teaching kitchens; making sure the egg incubators were working properly; poking at piles of rotting seaweed composting down for the farm’s potatoes; discussing lists of the very few ingredients, like flour, which need to be ordered in because the farm can’t produce enough for the school, with a chef jogging alongside us; picking wet walnuts; checking the locks on the greenhouses: all I was doing was following her around, taking pictures and making notes, and it was enough to leave me breathless, exhausted and craving a glass of something strong with ice in.

It was all rather brilliant. I left wanting to take up Darina as my new exercise regime.

There’s so much emphasis at Ballymaloe on the time and effort it takes to raise food properly. Cookery students “adopt” a fertilised chicken egg and watch the egg’s progression from potential scramble to chick to hen. Their first task at the school is to plant seeds (a large part of the grounds is given over to student vegetable plots) which grow into vegetables over their time at the school. Food raised with care and respect costs time and money; there are good reasons why you should be deeply suspicious of a £4 supermarket chicken. There is solar panelling (“Much more effective than they thought it would be, because of the reflections from the sea,” crowed Darina), rainwater collection, all that seaweed being used as a fertiliser (“We do not use cow muck from cows we do not raise ourselves. Who knows what they have been eating and what drugs they have ingested?”), a refusal to take up Government grants which might impact on the way things are done here, and more ethical responsibility in the stewardship of the land than you can shake a stick at. (Don’t, by the way. Darina will take it from you and use it for firewood in the bread oven.)

Because much of the food produced here is not being sold, but being used for teaching purposes, plenty of produce is made in the old-fashioned ways, exempt from EU legislation about temperature control, hairnets and bleach. So you’ll find a breezy barn whose ceiling is packed with hooks from which charcuterie dangles, a shed for cheesemaking with big fermentation tanks alongside cloth-wrapped cheeses stacked on the wooden shelves, and garlic drying in the sun.

Darina and the rest of the staff at the cookery school have done the seemingly impossible – turned traditional, ethical, methods of raising, marketing and cooking food into something that’s not so much a business as a movement that seems to be sweeping through Ireland. Ballymaloe is still one of the most respected places to train as a professional chef, but also runs short courses and afternoon demonstrations for amateurs – which I mean in the word’s strictest sense of those who are passionate – in food. If you’re the short-course holiday type, I can’t think of a lovelier or more inspiring place to spend your time.