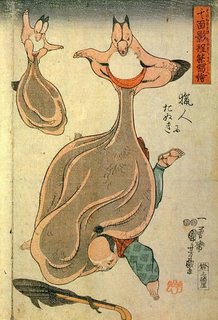

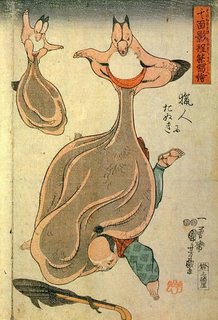

Two pieces of background cultural information before we begin. First up, a Tanuki is an alcoholic, raccoon-dog, Japanese trickster god, who (as in the picture to the right) has a habit of using his scrotum as a disguise, an umbrella, a weapon, a makeshift bivouac and so forth. (If you’re one of those for whom one classical Japanese scrotum-humour Tanuki woodcut is not enough, see this page to get your fill.) He’s also a patron god of bars…which leads us to point two. The Portland joint named for Tanuki is not exactly a restaurant. It’s a very tiny izakaya – a sake bar offering salty, spicy foods to accompany the drinks. And woe betide you if you turn up here expecting sushi, because you’ll be a) disappointed and b) liable to be beheaded by the angry whirling blades of Janis Martin, a chef who just happens to offer one of the best-value and most aggressively delicious omakase menus I’ve sampled. (Janis says it’s not, strictly, an izakaya, but an akachochin – a sort of dive bar. Don’t believe her. This is top-quality dining in a place that just looks like a dive bar.)

Two pieces of background cultural information before we begin. First up, a Tanuki is an alcoholic, raccoon-dog, Japanese trickster god, who (as in the picture to the right) has a habit of using his scrotum as a disguise, an umbrella, a weapon, a makeshift bivouac and so forth. (If you’re one of those for whom one classical Japanese scrotum-humour Tanuki woodcut is not enough, see this page to get your fill.) He’s also a patron god of bars…which leads us to point two. The Portland joint named for Tanuki is not exactly a restaurant. It’s a very tiny izakaya – a sake bar offering salty, spicy foods to accompany the drinks. And woe betide you if you turn up here expecting sushi, because you’ll be a) disappointed and b) liable to be beheaded by the angry whirling blades of Janis Martin, a chef who just happens to offer one of the best-value and most aggressively delicious omakase menus I’ve sampled. (Janis says it’s not, strictly, an izakaya, but an akachochin – a sort of dive bar. Don’t believe her. This is top-quality dining in a place that just looks like a dive bar.)

We pushed open the door to find a little room seating only 16, lighting that felt like a photographic darkroom, a blue fug of savoury, perfumed steam coming from the kitchen, a soundtrack of post-punk theremin music, and a TV balanced on top of the sake fridge showing a Japanese chef disembowelling herself. (Comedy, I think. These things don’t necessarily translate, but they’re sure as hell fascinating.) I am not usually prone to snap judgements, but from the moment the picture on the television changed to three rubberised Japanese zombies whose eyeballs kept falling out, I was pretty sure I was going to like Tanuki.

The menu embraces Okinawan, Japanese and Korean dishes, all designed to complement (and get you to order more) sake and beer. If you’re familiar with Korean seasoning and heat, you’ll be at home with what’s going on on the plates here. What’s on offer changes daily, but you can expect to find tofu made fresh in-house, real grated wasabi, local and impeccably raised meats, home-made pickles and some extravagantly weird spicing on the list every day.

Tanuki is pretty uncompromising; this is not a menu that panders to the daft and squeamish. ‘Crab brain’ miso, Japanese drinking vinegars and tiny duck hearts threaded on a bamboo skewer take pride of place. The bar is in-your-face scuzzy, the food designed to cram every taste bud you own with sensation. I chatted briefly with Janis about the off-beat setup here, and she mentioned something that drives me mad in Europe and clearly drives her mad in America too – the tendency of new ethnic restaurants to cater solely to high-end, top-class diners. None of your gleaming walls, shimmering waitresses and horrendously overpriced sushi here, more’s the joy. Somehow, I suspect that eel on a stick simply wouldn’t taste as good with a cloth napkin, anyway.

Order sake, and plenty of it. We chose a Korean gukhwaju – a rice wine flavoured with mountain chrysanthemum. Those intimidating-sounding drinking vinegars are actually delicious, and are a good non-alcoholic way to calm burning tongues; there’s only the slightest hint at an acidic fermentation behind a sweet mulberry, plum or strawberry syrupiness that seems designed to quench and soothe.

You can order directly from the menu, or pick a price-point for an omakase meal selected by the chef. We asked the waitress (helpfulness in human form – what I wouldn’t give for a dose of American service culture back in the UK) what sort of amount she recommended two hungry people spend, and she said that $20 a head should be plenty for a full meal. Ten courses later, we left reeling and plump. Two dollars a course per head!

Dishes seemed to get larger as the night progressed. We opened with a soft and meaty hamachi tuna sashimi, seasoned with some of that fresh wasabi and shoyu. We’d barely finished it when a dish of creamy and impeccably fresh uni sashimi (alive, says Janis, until the moment she orders it), on paper-thin slivers of lemon with sweet soy and more of that wasabi arrived. Hoshi kyui, a jellyfish, cucumber and wild herb salad in a hot and sour dressing, packed a fish-sauce umami bite that had us reaching for the drinks and then dipping straight back into the salad the moment we’d swallowed every mouthful. Skewered eel fillets in a sweet soy glaze, oily, salty and crisp, arrived fresh and hot from the grill, accompanied by some of the pickles that are made weekly in the kitchen.

Nasu to ebi nikkei was one of the larger dishes, and came with pearl-like sticky, short-grain polished rice. Elegantly de-veined shrimp, so fresh that they gave to the teeth with a crunch, were poached in a cinnamon tea, and served with a miso-dense eggplant and bok choi preparation. Things were starting to get seriously spicy by now, and our thoughtful server arrived with a pitcher of iced water.

The kitchen uses a huge number of different soy sauces. Shiro, tamari – you name it, it’s probably represented somewhere on the menu. We had two delicate, light meat balls made from wild boar, which came drenched with a gummy, sugary Korean soy.

Suki wagarashi nearly had me beaten. These pork ribs, cooked until the meat was falling stickily and glutinously from the bone, were rubbed in a Japanese mustard and sesame marinade that packed so much heat that I stopped being able to feel my lips. Fortunately, the next couple of courses stepped back from the spice a bit – lonngganisa, a fatty, porky Pinoy sausage, came sandwiched between two deliciously crisp and cooling slices of fresh grilled lotus root. And joy of joys – a baked char siu bun.

They saved the best, spiciest, saltiest and largest dish for last. Jajang bop – a huge claypot stuffed to the brim with steaming hot rice layered with shredded, salted, gelatinous pork, cubes of the kitchen’s fresh tofu and some unbelievably tasty fermented black beans. A raw egg lay on top with a generous portion of kim chee, dosed with a sinus-clearing amount of chillies, some fresh herbs and fat, long beansprouts. We stirred the bowl with chopsticks to scramble the egg through the hot rice, and kept on eating long after our distended stomachs and burning tongues were screaming to our brains to stop.

The lighting (and my fear of chefly beheading – Janis seems quite strict) stopped me from taking any pictures of what we ate, but there are plenty on Tanuki’s own website if you want to get a feel for the look of things; they’re very accurate depictions of what you end up eating. I only get to spend about one week a year in Portland, if that, and it’s fast becoming one of my favourite cities for eating in the world. Something has to be done about this parlous state of affairs; I wonder how the guys at Tanuki would feel if I turned up in their garden with a raccoon-dog-scrotum tent and set up house?

I have been skiing vigorously all day, and I’m as tired as a dog – so what you’re getting here is going to be a spot shorter than usual. Veritable Quandary (VQ to locals) is a bar and restaurant serving killer-fantastic cocktails, and food which is thoroughly decent if not extraordinary. It’s right next to the Hawthorne Bridge in Portland, with an excellent view of the Willamette river. Look out for the portrait on the inner wall of the conservatory featuring someone looking like a female, Victorian Charles Atlas.

Another time, I think I might be tempted to visit VQ for their drinks and bar snacks alone. I had one of those bar snacks as a starter – these dates (left), wrapped in pancetta and stuffed with goat’s cheese and Marcona almonds. Lovely sticky, sweet, salty, crispy, squashy things to nibble alongside a drink. Dr W’s snackish starter was a very tasty rabbit terrine (below), served with huge hunks of fresh, toasted brioche, a couple of mustards and some chutney.

Main courses thrilled me less. Barbecued boneless beef short rib was always going to be unsophisticated, but the saucing was altogether too much, and the meat itself felt sad and overdone (although this could have been a result of a too-fierce sauce masking the joint’s own flavour). The barley risotto it was perched on top of, though, was great, full of chunks of apple and roast butternut squash. Dr W’s steak was…a steak. A perfectly nice steak, although we both felt we could have happily swapped it and the short rib for a few more of those far more interesting starters.