I’m going to be in Prague until early next week. Blog posts will, hopefully, continue as usual, but this rather depends on whether the hotel has in-room Internet access. I am keeping my fingers crossed, and hope to be delivering you commentary on beer and dumplings tomorrow evening.

Pasta alla Medici

Now, while I might rail against Nigella Lawson’s approach to ham in cola, I am full of gratitude for her inclusion in Feast of a recipe for Pasta alla Medici, using any remaining ham you might have from the chunk you boiled the hell out of the day before. I’d last eaten it decades ago, and had been looking for a recipe ever since.

Now, while I might rail against Nigella Lawson’s approach to ham in cola, I am full of gratitude for her inclusion in Feast of a recipe for Pasta alla Medici, using any remaining ham you might have from the chunk you boiled the hell out of the day before. I’d last eaten it decades ago, and had been looking for a recipe ever since.

When I was twelve or so, a pamphlet was deposited on our school desks. It came from a company (pre-Internet, this) which would fix you up with a penfriend in a foreign country, depending on which boxes you ticked. (I don’t recall an ‘eating’ box to tick under the ‘hobbies’ heading; I think I ticked something typically precocious along the lines of ‘classical music’ and ‘visiting museums’. It is not surprising that girls on the school bus used to save pockets full of breakfast cereal to put in my hair every morning.)

There were also boxes to tick on the age, nationality and gender of your desired penfriend. Being newly possessed of all kinds of exciting hormones, and also possessed of a very overactive imagination, I decided that the thing every twelve-year-old English schoolgirl required for a full and satisfying life was a seventeen-year-old, Italian, male penfriend.

Fortunately, the penfriend company saw me coming, and allotted me a twelve-year-old girl. She was Italian, though, and she liked reading and music too, so we suited one another rather well, and wrote to each other (in English; my Italian remains limited to deciphering menus and asking the way to the museum) for years.

Eventually, Lisa and I had been writing to one another for such a long time that our parents decided we should visit each other. Her family lived in a beautiful flat in Genoa, where I went to school with her for a couple of weeks and discovered marron glace ice cream (my Mum had sent me to Italy saying sagely: ‘in Italy you can buy ice cream in every colour of the rainbow’, and I must have annoyed the hell out of Lisa’s family by obsessing about finding one in each colour).

Lisa’s Mum was a doctor, and didn’t have much time at home. When she was at home, she was not, in retrospect, a very engaged cook, and the Findus Crispy Pancake was my introduction to an Italian mother’s kitchen. Later that week we ate bollito misto (which translates roughly as ‘mixed boilings’, and was about as appetising as it sounds).

One thing, though, that Lisa’s mother cooked and cooked exceptionally well, was a really fabulous pasta dish, with sweet little peas, ham, and a creamy, buttery parmesan sauce. I asked her what it was called (although not for the recipe; my own mother didn’t like me cooking at home, since I did what I do now and sprayed the walls with food when cooking), and was delighted when she cooked it again twice before I left.

Pasta alla Medici is a very simple recipe, but is also, for some reason, a very hard one to find in books. I had to wait nearly twenty years before I came across Nigella Lawson’s recipe, and I am gushingly, pathetically grateful. She offers this three-person recipe as one which children will enjoy, and her portions are child-sized – make a larger amount if you’re feeding adults.

200g pasta

100g frozen petits pois

150ml double cream

150g diced ham

2 tablespoons grated Parmesan

Cook the pasta following the packet instructions, and after five minutes add the peas to the pasta water. When the peas and pasta are cooked, drain them. Warm the rest of the ingredients through in the pan you cooked the pasta in, then add the pasta and peas, toss to coat, and serve.

I added a few gratings of nutmeg to Nigella’s recipe. I also stripped some of the white fat off the ham I had cooked the day before and dry-fried it until crisp, adding a tablespoon of maple syrup and a pinch of cinnamon at the end, bubbling the syrup down to a caramel. I used this crisp, sweet crackling to dress the pasta. This is, however, mostly because I am greedy; you’ll probably be perfectly happy just eating the pasta on its own.

Ham in Coke

Several years ago, I stumbled on a Usenet post waxing lyrical about the savoury potential of Coca Cola when combined with pork. That same Coca Cola that your teachers spent years warning you about in the very darkest terms; at my school they used a can to dissolve a volunteer’s recently shed milk tooth away to nothing, and demonstrated its unholy ability to clean pennies with rotten-incisored glee.

Several years ago, I stumbled on a Usenet post waxing lyrical about the savoury potential of Coca Cola when combined with pork. That same Coca Cola that your teachers spent years warning you about in the very darkest terms; at my school they used a can to dissolve a volunteer’s recently shed milk tooth away to nothing, and demonstrated its unholy ability to clean pennies with rotten-incisored glee.

I have a caffeine-addicted husband and a yen to flout the outdated authority of my Home Economics teacher. I have spent several years perfecting a ham in cola recipe, and am more than mildly irritated to find that these days, Nigella Lawson is publishing a version of ham in Coke in every book she writes. No matter. Mine’s better. Ham needs something sweet and spicy to counter its savoury saltiness – it happens that cola is the perfect foil. I can’t think of another way I’d prefer to cook ham now – this may sound a perverse thing to do to a nice chunk of pork, but trust me; it’s fabulous.

You’ll need:

1kg smoked gammon

1-2 large bottles cola (more or less depending on the size of your pan)

1 red onion

1 bulb garlic

1 stick cinnamon

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

2 dried chilis

20 cloves (give or take a few)

1 teaspoon ground chipotle chili

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon ground mustard

4 tablespoons maple syrup

Place the gammon in a close-fitting, thick-bottomed pan (important, this thick bottom; you need to avoid singing the bottom of your ham) with the onion, halved, the bulb of garlic, cut in halves, the cinnamon stick, coriander seeds and whole chilis. Pour over Coke to cover (I’m afraid it has to be the full-fat version; Diet Coke won’t caramelise properly) and put on a medium heat until it reaches a simmer. Lower the heat enough to keep a gentle simmer, and put the lid on for 2 1/2 hours.

Place the gammon in a close-fitting, thick-bottomed pan (important, this thick bottom; you need to avoid singing the bottom of your ham) with the onion, halved, the bulb of garlic, cut in halves, the cinnamon stick, coriander seeds and whole chilis. Pour over Coke to cover (I’m afraid it has to be the full-fat version; Diet Coke won’t caramelise properly) and put on a medium heat until it reaches a simmer. Lower the heat enough to keep a gentle simmer, and put the lid on for 2 1/2 hours.

After your kitchen timer has gone, preheat the oven to 200c and lift the whole ham carefully from the liquid (Hang onto that liquid if you want to make Boston baked beans). Leave the ham to cool enough to handle. With a sharp knife, remove the rind, without removing the fat.

You’ll be left with a joint of meat with a glistening covering of fat. Use your sharp knife to score the top in diamonds, and stick a clove in each corner of each diamond. Make a paste from the ground cinnamon, ground chipotles, mustard powder and maple syrup, and brush it all over the ham, concentrating on the fatty surface. The sweet mixture will caramelise onto the crisping fat; this is pretty much 90% bad for you, but, unfortunately, it tastes approximately 100% good. I really should talk a friendly social statistician somewhere into working out just how bad for you things have to be to start tasting good; I’m sure there’s an interesting graph in that somewhere.

You’ll be left with a joint of meat with a glistening covering of fat. Use your sharp knife to score the top in diamonds, and stick a clove in each corner of each diamond. Make a paste from the ground cinnamon, ground chipotles, mustard powder and maple syrup, and brush it all over the ham, concentrating on the fatty surface. The sweet mixture will caramelise onto the crisping fat; this is pretty much 90% bad for you, but, unfortunately, it tastes approximately 100% good. I really should talk a friendly social statistician somewhere into working out just how bad for you things have to be to start tasting good; I’m sure there’s an interesting graph in that somewhere.

Put the whole ham in the oven, uncovered, for twenty minutes, remove and check that the fatty surface has formed a crust. (If you prefer more crust, put the ham under a high grill for two minutes.)

Put the whole ham in the oven, uncovered, for twenty minutes, remove and check that the fatty surface has formed a crust. (If you prefer more crust, put the ham under a high grill for two minutes.)

If you have made a large ham, you can make several good meals from it. Eat it like this, freshly cooked, with some sautéed potatoes; eat it in Pasta alla Medici; use it to flavour Boston baked beans.

If you’re having people round for dinner and feel like cheating, feel free not to mention the cola. And if you enjoyed this as much as I do, you’ll probably want to check out the sticky chicken pieces in coke too.

Onuga ‘caviar’

Caviar. It’s expensive, it’s delicious, and we’re being encouraged to avoid it to save the Beluga sturgeon from extinction. Being an impoverished fan of the pressed salted stuff, my little heart leapt on reading that Waitrose were stocking Onuga, a ‘completely natural . . . caviar substitute’, which, according to their advertorial piece, has a ‘smoky. . . clean, fresh taste’. The man behind it, Patrick Limpus, is full of the ethical values contained in his little black pots, and says: ‘I love caviar, which is why I’m so proud to have come up with a worthy – and delicious – substitute.’

Caviar. It’s expensive, it’s delicious, and we’re being encouraged to avoid it to save the Beluga sturgeon from extinction. Being an impoverished fan of the pressed salted stuff, my little heart leapt on reading that Waitrose were stocking Onuga, a ‘completely natural . . . caviar substitute’, which, according to their advertorial piece, has a ‘smoky. . . clean, fresh taste’. The man behind it, Patrick Limpus, is full of the ethical values contained in his little black pots, and says: ‘I love caviar, which is why I’m so proud to have come up with a worthy – and delicious – substitute.’

What follows is entirely my own fault. I used to work in magazine publishing, where one of my jobs was to edit adverts posing as real articles like this; I knew what the Waitrose magazine was doing, but I was still intrigued. I remained intrigued even when I looked at the tiny (and relatively expensive at £6) jar and read the words ‘reformed herring product’. It’ll be lovely little herring eggs, I posited. Dear little herring eggs that the nice man from the magazine has made salty and tasty for me. I love fish roe. I will walk miles for flying fish roe (tobiko) sushi (which is also a pretend fish roe product, not tasting of much on its own; the Japanese flavour and colour it until it’s something approaching manna), and I’d sell my soul for proper caviar. I knew I was going to be on my own at home all day on Sunday (Mr Weasel has to hand his thesis in on Wednesday, after several years of hard mathematical slogging, and is hiding in the lab polishing his diagrams), and decided I deserved a lunch of dear little herring eggs on blinis to cheer myself up in my solitude.

It started promisingly enough; the little black dots did look like fish roe, and on opening my precious jar I put one on the end of my finger, and licked. I pressed my tongue to the roof of my mouth, expecting the little egg to pop and release its delicious, oily juices . . . nothing. I chewed. Ah. That’s what they mean by ‘herring product’.

It started promisingly enough; the little black dots did look like fish roe, and on opening my precious jar I put one on the end of my finger, and licked. I pressed my tongue to the roof of my mouth, expecting the little egg to pop and release its delicious, oily juices . . . nothing. I chewed. Ah. That’s what they mean by ‘herring product’.

A little further reading revealed the true nature of my little jar of fishy punctuation marks. They’re reconstituted herring meat mixed with a seaweed product to make them gel into little balls, which are then salted and coloured with ‘vegetable carbon’. They taste like chewy taramasalata.

Onuga’s website makes it pretty clear that the emphasis in developing the product was on the mimicing the appearance rather than the flavour (or the incredibly important texture) of true caviar. ‘Onuga . . .’, they say, ‘. . . not only looks like the real thing but it tastes delicious too’. Delicious. Not ‘like caviar’. They claim it’s effortlessly superior in taste and texture to plain old lumpfish roe, which at least pops for you, rather than rolling round and round your mouth like pellets of fishy denture fixative.

The flavour is pleasant, but I feel I’d have been a bit better off with a tub of Waitrose’s very good premium taramasalata, or with a pack of smoked salmon. The texture is a disaster.

The flavour is pleasant, but I feel I’d have been a bit better off with a tub of Waitrose’s very good premium taramasalata, or with a pack of smoked salmon. The texture is a disaster.

I’ve made twelve blinis. After piling all of them with creme fraiche, Onuga and chives, I eat three, and then I do something unheard of in this house – I throw the rest away.

Wild carrot – and violets in November!

This week’s Weekend Herb Blogging post (organised by Kalyn from Kalyn’s Kitchen) couldn’t be conducted from the garden, because most of the garden is either hidden under mulch or looking very, very sorry for itself at the moment. Winter finally arrived in earnest last week; our absurdly long, warm autumn (something to do with African winds, according to the weather forecasters) has gone, those warm winds replaced by something much less friendly from the north. It’s freezing, but very beautiful. Time to take a quick picture of the ruined church next door, and go and find some herbs growing wild somewhere.

This week’s Weekend Herb Blogging post (organised by Kalyn from Kalyn’s Kitchen) couldn’t be conducted from the garden, because most of the garden is either hidden under mulch or looking very, very sorry for itself at the moment. Winter finally arrived in earnest last week; our absurdly long, warm autumn (something to do with African winds, according to the weather forecasters) has gone, those warm winds replaced by something much less friendly from the north. It’s freezing, but very beautiful. Time to take a quick picture of the ruined church next door, and go and find some herbs growing wild somewhere.

We live at one end of the Devil’s Dyke, an Anglo-Saxon earthwork which stretches for seven miles in a perfectly straight line. It’s an internationally important Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI); the chalk grassland along the length of the dyke is untouched and provides an environment for some very rare plants and animals, including the pasque flower, lizard orchid (which smells dreadful when in flower – a lot like unclean stables) and the exceptionally rare chalkhill blue butterfly. It’s a great place to walk and find plants, and there are usually very few other people out walking along it, so it’s very a peaceful and pleasant way to spend an afternoon.

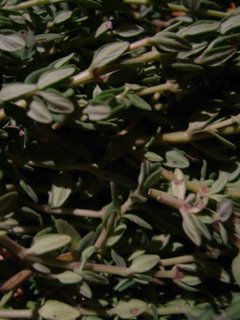

The very warm autumn has meant that some plants along the dyke have become confused and are flowering now, when they should be flowering in the spring. I found this violet (in a clump with several others, all pushing boldly through the frost) flowering several months early, not having realised it’s November. Violets are a lovely plant to cook with; I’m currently on the lookout for some violet essence to flavour fondants with at Christmas (at the moment it looks like I’m going to have to send away to France for it), and the flowers, crystalised, are beautiful as well as delicious. These violets were smelling glorious. The leaves and root as well as the flower carry the soft, powdery scent, and can also be used in cooking; the leaves are slightly tart but scented, and can be used in a salad or made into a tea, and the roots are used medicinally in cough syrups. It’s very sad to see them flowering now, knowing the frost will kill them in a couple of days; I look forward to the violets in the garden flowering next year.

The very warm autumn has meant that some plants along the dyke have become confused and are flowering now, when they should be flowering in the spring. I found this violet (in a clump with several others, all pushing boldly through the frost) flowering several months early, not having realised it’s November. Violets are a lovely plant to cook with; I’m currently on the lookout for some violet essence to flavour fondants with at Christmas (at the moment it looks like I’m going to have to send away to France for it), and the flowers, crystalised, are beautiful as well as delicious. These violets were smelling glorious. The leaves and root as well as the flower carry the soft, powdery scent, and can also be used in cooking; the leaves are slightly tart but scented, and can be used in a salad or made into a tea, and the roots are used medicinally in cough syrups. It’s very sad to see them flowering now, knowing the frost will kill them in a couple of days; I look forward to the violets in the garden flowering next year.

Further along the dyke, I found the dead seedhead of a wild carrot. This is the ancestor of the carrot you grow and eat at home; it has a tap root like the modern carrot, but this tap root is white and more spindly than the carrots we use. (You may know this plant by its colloquial name, the Bee’s Nest.) Pick the root young if you want to eat it; it quickly becomes too woody to be eaten.

Further along the dyke, I found the dead seedhead of a wild carrot. This is the ancestor of the carrot you grow and eat at home; it has a tap root like the modern carrot, but this tap root is white and more spindly than the carrots we use. (You may know this plant by its colloquial name, the Bee’s Nest.) Pick the root young if you want to eat it; it quickly becomes too woody to be eaten.

The whole plant, when green and juicy, smells aromatic and carroty, although the root is not as tasty as the cultivated sort, being rather bitter. The whole leafy part of the plant can be used in a tea, and used to be used widely as a medicinal herb, as it is rather diuretic. It can also be added as a cooking herb in stews, giving a fragrant, carroty flavour.

The wild carrot’s seeds are also used in cooking and folk medicine; they have a warm and toasty taste and are good on top of breads. The flower heads, when fresh, can be battered and fried like elderflower heads, and are really delicious; I’ll write a post on them in the summer.

Next weekend’s herb blogging is going to be awkward and will require some thought – I shall be in Prague for the Christmas markets. I hope the hotel has Internet access – watch this space!

Literary cocktails

I am female and approaching 30 at a headlong rush. This means I like cocktails. I am fortunate, then, in living near Cambridge, where the River Bar and Kitchen perches above the river, over a gym whose window gives a splendid view of a hot tub full of svelte ladies which you have to sidle past to get to the bar.

I am female and approaching 30 at a headlong rush. This means I like cocktails. I am fortunate, then, in living near Cambridge, where the River Bar and Kitchen perches above the river, over a gym whose window gives a splendid view of a hot tub full of svelte ladies which you have to sidle past to get to the bar.

The Kitchen part of the River Bar and Kitchen is not as glorious as the Bar part, so I’ll gloss over it; I ate there with some friends a couple of weeks ago and was rather disappointed (dry meats, vinegary preparation, identikit saucing). The cocktails, though, are well worth a visit.

A few months ago, gurgling happily over a Manhattan (equal measures bourbon and vermouth, with a cherry and some orange zest and a dash of bitters), I was told by a friend with something pink and creamy on the end of her nose that I only like pretentious grown-up cocktails. I think this means that I prefer cocktails which aren’t sugary and full of things squirted out of a cow, but I will admit to a certain mental frailty – I get a tiny kick (OK, a massive one) out of the Literary Cocktail. Knowing which brand of lime cordial you should use to make a Gimlet like the kind Philip Marlowe enjoyed, and being able to argue with the barman about it. That kind of thing.

The drink at the top of the page is a perfect example of pretension in cocktail form, and it’s my very favourite cocktail, the alcoholic drink I would happily forgo all others for; a Vesper Martini. This is the original Martini James Bond creates in Casino Royale (1957, the first Bond book), named for Vesper Lynd, Bond girl and double agent. He instructs the barman:

‘In a deep champagne goblet . . . Three measures of Gordon’s, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel.’

Bond knew what he was talking about; this is a beautiful cocktail.

Kina Lillet is a vermouth, and the guy at the River Bar uses only a tiny breath of vermouth; he says tastes have changed since the 50s. (They certainly have; Tom Lehrer sang about ‘Hearts full of youth/Hearts full of truth/Six parts gin to one part vermouth‘ in Bright College Days, and this is a very vermouth-y Martini indeed to my youthful, truthful tongue.)

My next Martini was a Zubrowka (a vodka flavoured with fragrant bison grass, which is added during distillation) one. I have a great love for W Somerset Maugham. In The Razor’s Edge, Isabella says:

My next Martini was a Zubrowka (a vodka flavoured with fragrant bison grass, which is added during distillation) one. I have a great love for W Somerset Maugham. In The Razor’s Edge, Isabella says:

‘It smells of freshly mown hay and spring flowers, of thyme and lavender, and it’s soft on the palate and so comfortable, it’s like listening to music by moonlight.’

Even though her ultimate aim in rhapsodising about the stuff is to drive another character to a sodden alcoholic grave, I can’t help but feel Maugham himself must have been pretty keen on Zubrowka too. (Another Somerset Maugham favourite was avocado ice cream, which is, you may be surprised to learn, absolutely divine – watch this space.)

For some reason I can’t fathom, some apple schnapps and other fruity stuff found its way into my Martini when I wasn’t standing at the bar to keep a firm hand on the barman (there really shouldn’t be anything other than gin or vodka and vermouth – find me the man who invented the chocolate martini and I will show you an man without tastebuds but with an uncanny understanding of what drunk women will pay for), but it was still pretty fabulous. Excuse the lipstick on the rim in the photograph. It is hard to remember to photograph your Martini before drinking it when you’ve already had a few.

My friends were now on the champagne cocktails. In the back here is a Carol Channing. Those who have seen Thoroughly Modern Millie, a glorious film with Julie Andrews, Mary Tyler Moore, James Fox and a biplane, will remember Carol Channing’s dance with the xylophone and her habit of shouting ‘Raspberries!’ A Carol Channing is made with muddled raspberries, sugar syrup, Chambord and raspberry eau de vie, topped up with champagne.

My friends were now on the champagne cocktails. In the back here is a Carol Channing. Those who have seen Thoroughly Modern Millie, a glorious film with Julie Andrews, Mary Tyler Moore, James Fox and a biplane, will remember Carol Channing’s dance with the xylophone and her habit of shouting ‘Raspberries!’ A Carol Channing is made with muddled raspberries, sugar syrup, Chambord and raspberry eau de vie, topped up with champagne.

In front is a proper champagne cocktail – that is to say bitters soaked into a brown sugar lump, with champagne poured on top. A lovely drink, and a very, very old fashioned cocktail; it first pops up in 1862 in Jerry Thomas’s How to mix drinks. (Click the link for an online facsimile of the book.) There are only a very few true cocktails in the book (the other recipes are flips, juleps, punches and recipes for flavoured syrups and so forth), and the champagne cocktail is the only one you’re likely to recognise in 2005.

Somebody (as the evening wore on I lost track of who was ordering what. Can’t think why) ordered a Mojito (muddled mint and sugar, rum, lime and soda water). A Brazilian friend has special mint-muddlin

Somebody (as the evening wore on I lost track of who was ordering what. Can’t think why) ordered a Mojito (muddled mint and sugar, rum, lime and soda water). A Brazilian friend has special mint-muddlin

g pots and sticks, like a conical mortar and pestle, for making these; she brings cachaça, a Brazilian rum, home to England when she visits her family, and uses it to makes the best Mohitos and Caipirinhas (lime, soda, cachaça and sugar) I’ve tasted.

I should wrap this post up. Mr Weasel is on his way home from the supermarket; he has gone to fetch a bottle of Big Tom’s tomato juice, which we will adulterate with some vodka I’ve been steeping chilis in for a few months. I love weekends. Those wondering about the Philip Marlowe Gimlets, by the way, should read The Long Goodbye, where Marlowe informs us that ‘A real gimlet is half gin and half Rose’s Lime Juice, and nothing else. It beats martinis hollow.‘ He’s right; Rose’s is the only one made only with real, fresh limes. Try it some time – cut down on the Rose’s if you find it too sweet.

Buffalo wings

Another item from the Great American Suitcase Load of Food I brought back last February was a large bottle of Frank’s Hot Sauce. Frank’s is the traditional sauce used for gorgeous, buttery, spicy Buffalo wings; unfortunately it’s hard to find the dish or the sauce readily in the UK, so you’ll have to resort to importing sauce and making your own wings.

Another item from the Great American Suitcase Load of Food I brought back last February was a large bottle of Frank’s Hot Sauce. Frank’s is the traditional sauce used for gorgeous, buttery, spicy Buffalo wings; unfortunately it’s hard to find the dish or the sauce readily in the UK, so you’ll have to resort to importing sauce and making your own wings.

We’re in luck; chicken wings, being bony and a little unprepossessing, are not something the English, who seem to prefer meat that comes in boneless, skinless chunks, buy very often. While they’re usually available in the shops, they’re not expensive. This is great news for me; there are plenty of excellent Chinese chicken wing recipes (when I was little we’d fight over the wings, which my Dad always assured us were where the very tastiest, most succulent meat was), and I have an artery-clagging love for Buffalo wings with blue cheese dip and celery. I decided to break into my bottle of Frank’s, and pay no attention to the calories.

You’ll need to joint your chicken wings. It’s extremely easy; you just need a sharp knife. This wing is whole – spread it out and look for the two joints. Mr Weasel, taller, stronger and kinder than me, suggested that his extra height would make the jointing easier. Shamefully, I stood back, beaming, and let him do it. I really don’t enjoy handling raw chicken very much; I’m usually fine with raw meats, but for some reason I find chicken a bit difficult. There’s something about the way it smells raw which makes me enjoy the cooked product less. Poor thing; he does work for his supper. The joints themselves are softer than the bone itself, so your knife should penetrate cleanly and neatly.

You’ll need to joint your chicken wings. It’s extremely easy; you just need a sharp knife. This wing is whole – spread it out and look for the two joints. Mr Weasel, taller, stronger and kinder than me, suggested that his extra height would make the jointing easier. Shamefully, I stood back, beaming, and let him do it. I really don’t enjoy handling raw chicken very much; I’m usually fine with raw meats, but for some reason I find chicken a bit difficult. There’s something about the way it smells raw which makes me enjoy the cooked product less. Poor thing; he does work for his supper. The joints themselves are softer than the bone itself, so your knife should penetrate cleanly and neatly.

Chop through both joints like this, and discard the wing tip. You’ll end up with a little drumstick-looking bit, and one with two little bones (much like your forearm, if you, like me, can only remember which bits of meat are where on an animal by comparing the animal with yourself).

Chop through both joints like this, and discard the wing tip. You’ll end up with a little drumstick-looking bit, and one with two little bones (much like your forearm, if you, like me, can only remember which bits of meat are where on an animal by comparing the animal with yourself).

Heat deep oil for frying to 190c (375f). I use a wok and a jam thermometer for deep frying; the wok means you use less oil, and having a wide container means you can fry more wings at once. Fry the winglets in batches ( I did six at a time) until they are golden brown.

When one batch of wings is ready (they should be about this colour), put them to drain on some kitchen paper in a very low oven, where they can keep warm until all their friends are ready. I cooked fifteen wings (so thirty chopped up wing bits), which should serve three people.

When one batch of wings is ready (they should be about this colour), put them to drain on some kitchen paper in a very low oven, where they can keep warm until all their friends are ready. I cooked fifteen wings (so thirty chopped up wing bits), which should serve three people.

Meanwhile, you can get to work on the blue cheese dip while your sous chef gets on with cutting celery into strips. I used a recipe given to me by an American friend, which I’ve further messed about with and added to a bit; I think it’s pretty much perfect:

1 cup sour cream

1 cup mayonnaise

1/2 cup crumbled blue cheese (use the strongest cheese you can find; for me, this time round it was Gorgonzola, but Roquefort’s great in this too)

1 tablespoon cider vinegar

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 grated shallot

1 clove grated garlic

1 handful fresh herbs, chopped finely (I used parsley and chives)

2 teaspoons Chipotle Tabasco sauce (use regular Tabasco if you can’t get the lovely smokey Chipotle version)

Salt and pepper to taste.

Easy as pie; just mix the lot up together.

Easy as pie; just mix the lot up together.

Now warm half a bottle of that Frank’s hot sauce, transported across continents wrapped in your knickers like precious jewellery, with half a pat of butter. When the butter is melted, whisk it all together. Pour the lot over the crispy little winglets in a deep bowl, and toss like a divine salad.

Serve with the blue cheese dip and the sticks of celery. You’ll make a terrible mess; have lots of napkins on the table.

I really must find out who the hell this Frank fellow with the sauce is, find him and shake his hand.

Canteloupe and winter melon ice cream

Apologies for the lack of a post last night; one of my friends had his UK Citizenship ceremony yesterday, and we were out late celebrating. (When I got home, I was arguably not in a fit state to be allowed anywhere near a keyboard.) This means you get an early morning, pre-work post.

Apologies for the lack of a post last night; one of my friends had his UK Citizenship ceremony yesterday, and we were out late celebrating. (When I got home, I was arguably not in a fit state to be allowed anywhere near a keyboard.) This means you get an early morning, pre-work post.

Buying the melons for this ice cream was an interesting experience. I was casting around the supermarket for some fruit to turn into an ice cream, and saw a stack of canteloupes. Next to it was a second stack of canteloupes; these were nearly half the price. Why could this be? I picked up an expensive one. It smelled fragrant and melony, even through the skin. I picked up a cheap one. It smelled like a potato.

I don’t like potato ice cream, even potato ice cream that’s a pretty melon colour, so I went for the expensive ones.

To make this ice cream you will need:

2 canteloupe melons, seeds and skin removed

1/2 pint milk

2 egg yolks

4 tablespoons honey

1 pack crystalised winter melon (see below)

2 drops vanilla essence

I started by making a custard as a base; the milk was brought to a near-simmer with the vanilla and honey (from a jar of local honey from bees from the next village), and the egg yolks were beaten in until the mixture thickened. I then pureed the melons in the Magimix, then passed them through a sieve into the custard, folded everything together, and added the winter melon, cut into tiny pieces. Refrigerate the mixture, then follow the instructions on your ice cream maker.

Candied winter melon was my favourite Chinese sweets when I was a little girl. On trips to London I would bully my parents into going to Chinatown to visit the supermarkets, so I could take a pack home. It’s tooth-achingly sweet, and the melon has a slightly crisp texture, like a water chestnut. If you’re near a Chinese supermarket, do try to get your hands on a pack for this recipe; you could also substitute Italian candied melon, but this is so good that it would be a shame if you couldn’t try it.

Candied winter melon was my favourite Chinese sweets when I was a little girl. On trips to London I would bully my parents into going to Chinatown to visit the supermarkets, so I could take a pack home. It’s tooth-achingly sweet, and the melon has a slightly crisp texture, like a water chestnut. If you’re near a Chinese supermarket, do try to get your hands on a pack for this recipe; you could also substitute Italian candied melon, but this is so good that it would be a shame if you couldn’t try it.

Winter melon grows in the summer, but has a waxy skin which means it will keep for many months, giving it its name. It’s used in Chinese cooking as a vegetable (if it’s not candied, it’s not very sweet; it’s really a gourd and not a sweet melon); it has a crisp texture and is a good carrier of flavours. Once candied, it’s sublimely good.

I was hoping to garnish the ice cream with winter melon pieces as well, but unfortunately we’d eaten the few I kept to one side by the time the ice cream was ready. (I defy you to be able to leave unaccompanied winter melon in your kitchen for long without accidentally eating it.) It was delicious; Mr Weasel made gurgling noises and said ‘it tastes like sweeties’. Most of the ice cream is now in the freezer, so we can keep people happy at Christmas.

I was hoping to garnish the ice cream with winter melon pieces as well, but unfortunately we’d eaten the few I kept to one side by the time the ice cream was ready. (I defy you to be able to leave unaccompanied winter melon in your kitchen for long without accidentally eating it.) It was delicious; Mr Weasel made gurgling noises and said ‘it tastes like sweeties’. Most of the ice cream is now in the freezer, so we can keep people happy at Christmas.

Beef and Guinness casserole

My Dad told me a while ago that he doesn’t enjoy stews and casseroles which use stout as a base; he finds them, he said, bitter. This is an opinion shared by a lot of people, and it’ s such a shame; the only reason the stout casseroles you’ve eaten in the past have been bitter has to do with length of time in the oven. Cooked at a low temperature for several hours, the beer will magically turn into a rich, sweet and glossy sauce, and there won’t be a hint of bitterness. Promise.

My Dad told me a while ago that he doesn’t enjoy stews and casseroles which use stout as a base; he finds them, he said, bitter. This is an opinion shared by a lot of people, and it’ s such a shame; the only reason the stout casseroles you’ve eaten in the past have been bitter has to do with length of time in the oven. Cooked at a low temperature for several hours, the beer will magically turn into a rich, sweet and glossy sauce, and there won’t be a hint of bitterness. Promise.

The preparation of this dish doesn’t take too long, but you’ll need to leave it in the oven for at least three hours – if making if for lunch, I usually make it the night before, leave it in the fridge overnight and reheat. Like many casseroles, it improves with keeping.

Stout, for those who are only familiar with good old Guinness, is a generic term for a very dark, heavy beer made with roasted malts and barley. You can use any stout; it doesn’t have to be Guinness. Stout has a toasty, dry flavour; buy a couple of cans to drink with the meal.

I used:

I used:

2 1/2 lb rump steak, cubed

3 red onions, quartered and split into layers

2 cans Guinness (or other stout)

1 tablespoon fresh thyme

4 cloves garlic, squashed

1 jar of pickled walnuts, halved

2 tablespoons of juice from the walnut jar

2 tablespoons flour

Olive oil

Salt and pepper

Pickled walnuts are another curiously English thing; walnuts picked before they are ripe and pickled whole in a sweetened vinegar. They’re perfect with sharp English cheeses like cheddar; sweet and tangy, with a lovely nutty aroma. I use Opie’s pickled walnuts; they do look like tiny roast mouse brains (that’s one in the photo at the top, nestling to the right of the meat and kind of indistinguishable from it), but they’re extremely good. Leave them out if you can’t find any (English supermarkets carry them all year round with the other pickles), and add the juice of a lemon and a tablespoon of sugar instead.

Preheat the oven to a very low setting (140c/275f).

Brown the meat in olive oil in small batches. (In the picture on the right, it’s just been browned. There is only half a glass of Guinness because I have drunk the rest of the can already. Oops.) Use the pan you’ll be cooking the casserole in, over a high flame, and remove the browned meat to a dish. You can really go to town with the browning; you want a good deep brown, almost charred finish to give the flavour depth. When the meat is removed from the pan, add some more olive oil, and add the onions to the pan, stirring them until their edges are also a little charred. Return the meat to the dish with its juices, and stir in the flour (which will help to thicken the sauce). Continue stirring for a minute, then add both cans of Guinness, the herbs and garlic, and the pickled walnuts and their juice. Season, bring to a simmer (hard to spot, this; Guinness gets very frothy when you make it hot), and then put the lid on and put the dish in the oven.

Brown the meat in olive oil in small batches. (In the picture on the right, it’s just been browned. There is only half a glass of Guinness because I have drunk the rest of the can already. Oops.) Use the pan you’ll be cooking the casserole in, over a high flame, and remove the browned meat to a dish. You can really go to town with the browning; you want a good deep brown, almost charred finish to give the flavour depth. When the meat is removed from the pan, add some more olive oil, and add the onions to the pan, stirring them until their edges are also a little charred. Return the meat to the dish with its juices, and stir in the flour (which will help to thicken the sauce). Continue stirring for a minute, then add both cans of Guinness, the herbs and garlic, and the pickled walnuts and their juice. Season, bring to a simmer (hard to spot, this; Guinness gets very frothy when you make it hot), and then put the lid on and put the dish in the oven.

Three hours later, you’ll have a rich and unctuous casserole. The meat will be incredibly tender, dark brown and full of juices. I served it with some mashed King Edward potatoes, with quarter of a pint of boiling milk beaten into them, some truffle-infused olive oil and a sprinkling of thyme. I’d like to try making this with Young’s Chocolate Stout some time; there’s a world of chocolate beer out there just crying out to be cooked with.

Twice-baked garlic and herb potatoes

A few weeks ago, I mentioned that the pub baked potato, a horrid thing which usually comes with a raw, solid middle, a charred outside, and insufficient cheese, does its genre a great disservice. The baked potato can be fantastic; a thing of creamy beauty.

A few weeks ago, I mentioned that the pub baked potato, a horrid thing which usually comes with a raw, solid middle, a charred outside, and insufficient cheese, does its genre a great disservice. The baked potato can be fantastic; a thing of creamy beauty.

American readers whill be shocked to learn that I had never come across the twice-baked potato until February this year, when, skiing in Nevada, I had a sudden and terrible craving for carbohydrates. A nice man agreed to sell me a steak with a choice of accompaniments, among which was a twice-baked potato. I had to ask what it was. He looked at me as if I were wearing an even stupider hat than I actually was, and explained that the twice-baked potato is a potato baked as normal, with the fluffy flesh scooped out and mixed with butter and other good things, placed back into the shell, and baked again until piping hot.

When the nights are cold, dark and depressing, some fresh herbs in your dinner will work magic in making you feel summery. I used flat-leaved parsley, tarragon and chives. I wanted the potatoes’ flesh to be really fat and creamy, so looked out for some full-fat cream cheese to beat into them. Full of cheeses, butter and all those carbs, this is not a slimming recipe – but then again, if you want to keep the cold out, you’ll need a layer of fat under your jeans. For four potatoes you’ll need:

When the nights are cold, dark and depressing, some fresh herbs in your dinner will work magic in making you feel summery. I used flat-leaved parsley, tarragon and chives. I wanted the potatoes’ flesh to be really fat and creamy, so looked out for some full-fat cream cheese to beat into them. Full of cheeses, butter and all those carbs, this is not a slimming recipe – but then again, if you want to keep the cold out, you’ll need a layer of fat under your jeans. For four potatoes you’ll need:

4 baking potatoes

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 pack garlic and chive cream cheese

1 pack unflavoured cream cheese

1 clove garlic, crushed into a paste

1 handful each tarragon, chives and parsley, chopped roughly

2 tablespoons butter

8 tablespoons grated cheddar cheese

Salt

Rub the potatoes with the olive oil, and sprinkle with a coarse-grained salt. Bake at 200C (450 F) for an hour and a quarter. When they’re done, slice them in half and, holding the potato in an oven glove, scoop out the flesh. You’ll be left with a nice little potato-skin container.

Rub the potatoes with the olive oil, and sprinkle with a coarse-grained salt. Bake at 200C (450 F) for an hour and a quarter. When they’re done, slice them in half and, holding the potato in an oven glove, scoop out the flesh. You’ll be left with a nice little potato-skin container.

Combine the soft potato flesh with the cream cheeses, herbs and garlic in a large mixing bowl, and thrash about it with a fork until everything is combined. You don’t want a completely smooth mixture; just make sure all the ingredients are dispersed equally. Don’t salt the mixture; there will be enough salt in the cheeses, and you’ll also be able to taste the salt on the lovely crispy skins.

Pile the mixture into the potato skins in the dish you baked them in, and sprinkle the cheese over evenly. Put everything back in the oven for another twenty minutes. Eat with or without a ski hat, but do try not to spend so long taking photographs that they go cold.

Pile the mixture into the potato skins in the dish you baked them in, and sprinkle the cheese over evenly. Put everything back in the oven for another twenty minutes. Eat with or without a ski hat, but do try not to spend so long taking photographs that they go cold.