If you’d asked me last week, I’d have said that it was impossible to accidentally book a table at a two-star chef’s new restaurant while remaining firmly under the impression that you were booking something quite different. My poor Dad, on phoning to confirm the table at what used to be one of his favourite restaurants, even started the conversation with: “Hello. Is this Lundum’s?” And the person picking up said “Yes.” (The correct answer would have been “No. Lundum’s closed six months ago. This is l’Ambassade de L’Ile.”) The waiter did acknowledge that we are not the first party this has happened to. It’s a bad way to start a meal, and I hope they sort things out at their reservations desk; l’Ambassade has no need to rely on the reputation of the excellent restaurant that used to occupy this building, and everyone in our group started the evening extremely irritated at the mix-up.

If you’d asked me last week, I’d have said that it was impossible to accidentally book a table at a two-star chef’s new restaurant while remaining firmly under the impression that you were booking something quite different. My poor Dad, on phoning to confirm the table at what used to be one of his favourite restaurants, even started the conversation with: “Hello. Is this Lundum’s?” And the person picking up said “Yes.” (The correct answer would have been “No. Lundum’s closed six months ago. This is l’Ambassade de L’Ile.”) The waiter did acknowledge that we are not the first party this has happened to. It’s a bad way to start a meal, and I hope they sort things out at their reservations desk; l’Ambassade has no need to rely on the reputation of the excellent restaurant that used to occupy this building, and everyone in our group started the evening extremely irritated at the mix-up.

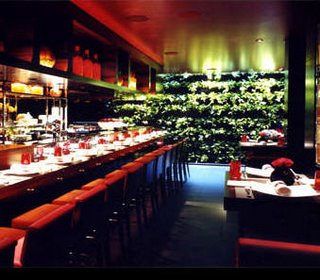

Still: on getting there, we decided to stay; we had all, after all, travelled between two and three hours to get there, we were seduced by the colour scheme (aubergine shag-pile carpet! White panels of leather with what looked like a dear little belly button in the middle of each one!), and I’d read about the chef, Jean-Christophe Ansanay-Alex before. I was secretly rather thrilled to have the chance to try his cooking. His L’Auberge de l’Ile in Lyon has two stars; he used to cook for Christina Onassis; he only has one arm. Prices here are extraordinarily high, but we were celebrating; it’s nearly Christmas; and I’ve been cooking tofu, pork hock and oxtail and other budget proteins for weeks, so was feeling like a bit of cream and truffles. The à la carte had numbers on it which looked to be denominated in rupees rather than pounds (no starter came in under £25), so we all went for the £90 tasting menu, reasoning that three à la carte courses weren’t going to come in at much less than that.

I’m still a little uncomfortable about the price, especially given that we fully intended to pay for our half, but had our credit card batted away by my Dad, who gets into Father Christmas mode at this time of year. £90 (without wine from the pricey list – and my Kir Royale alone cost £15) seems a hell of a lot to pay for a meal in the current financial climate, especially when you find yourself picking your way through a clot of tramps swigging lager outside South Kensington tube station on your way home.

Ansanay-Alex’s tasting menu does, at least, try as hard as it can to justify its price. It’s almost a pastiche of Lyon’s rich, buttery, creamy cuisine, and there’s a sense that somebody has sat down with a checklist of the most expensive ingredients, making little ticks as he works his way down through scallops, lobster, caviar, white truffles, black truffles and foie gras. The problem with constructing a menu like this is that all sense of balance goes out of the window, with creamy veloutes, buttery Béarnaises and sabayons, absurdly dense reductions and heavy, rich farces rampaging through the menu like a herd of oily buffalo.

L’Ambassade is generous with amuse bouches at the start of the meal and with friandises at the end. A heap of herbs fried in a tempura batter arrives before you’ve even ordered, and our amuses included a really lovely croquette of black pudding in a cider reduction alongside a tiny clam shell filled with a truffly mirepoix of sweet vegetables, topped with the poached clam.

The menu opens as it means to go on – with a mind to the eventual death of your liver. A velvet-smooth cream of scallop soup had a mosaic of lobster-marinaded scallop slices and squares of melting butter resting on the surface. A teaspoon of caviar (the farmed French variety) was inserted into a soft-boiled hen’s egg, surrounded by a thankfully tart lemon sabayon. Sea bass, its oily skin cooked to a salty, crisp bark, sat on a fondant potato (always a show-off accompaniment – they’re hard to cook well, and are a tremendously chefly thing to put on a plate), sitting in an ornamental pond of really dense, buttery Béarnaise, full of a tiny dice of clams and tomatoes. Venison loin, wrapped in a caul with a foie and black truffle farce, was bathed in London’s densest jus. The tiny tower (why is it always towers?) of beetroot and pear was a joyous contrast to all this richness – but oh, so small. At this point I would have paid almost anything for a salad.

Another soup – this time a chestnut veloute with celery leaves, crisp little puffs of parmesan and a slice of white truffle. It’s white truffle season at the moment, and the smell as the dishes approached was glorious. Some white truffle oil was drizzled into the dish – gorgeous, but I wish this buttery, sweet, creamy, nutty, truffly concoction had been served at the start of the meal, when my appetite for all this richness still had legs.

Coffee tart, peanut ice cream, a little disk of hazelnut meringue. “I wish there was some fruit,” said Dr W. “The cream-tasting bit of my tongue doesn’t work any more.” Everyone at the table concurred heartily. (And the pastry in that tart was the single dud of the evening – cakey and rather solid.) We thought this was the end, but the food just kept on coming – a positive bucket full of salt caramels, most of which found their way into my Mum’s handbag; fresh, hot, citrusy Madeleines; almond macarons with a fresh, creamy chocolate truffle centre. Finally, here were cones of gingerbread filled with liquorice ice cream, topped with a hard caramel shaped like, and flavoured with, star anise. This was the lightest, most digestible item we ate. So much so that I gave mine to Dr W to digest.

The (gargantuan) bill arrived sealed with a dollop of aubergine-coloured wax.

This is gorgeous, beautifully presented food, and it’s so French I was fully expecting it to go on strike. But it’s all a little too much at once – this is rich stuff in every sense of the word, and I wonder how it’s going down during the credit crunch. I’d certainly expect a restaurant of this calibre to be far, far more busy on a night shortly before Christmas than it was when we visited. If you’re set on visiting, try lunchtime, when a two-course menu comes in at £25, and a three-course one at £30.

Does anyone know where I can buy some aubergine shag-pile carpet?