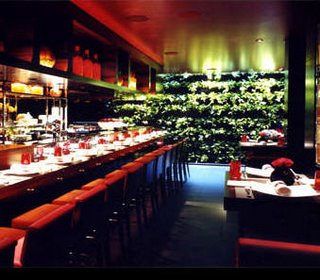

A confession – I have a (probably pathological) dislike of writing about my absolute favourite restaurants here. There aren’t that many which fall into that category; a couple in London, a couple in the US, a couple – OK, more than a couple – in France; but there’s an unpleasantly selfish part of me which really, really doesn’t want to share. It’s irrational, and lately I’ve pledged to get the hell over this particular issue, which is good news for you, because you are finally getting to read about places I keep returning to, like L’Atelier de Joel Robuchon and Le Gavroche (the pic is pinched from Wikimedia Commons – I hate bringing a camera to places like this). You’ll also get to read about several of my favourites, so far jealously unshared, in October, when Food Journeys of a Lifetime: 500 Extraordinary Places to Eat Around the Globe is released – it’s a National Geographic publication, and 20 of those extraordinary places were written about by me. More on that when the book finally comes out.

A confession – I have a (probably pathological) dislike of writing about my absolute favourite restaurants here. There aren’t that many which fall into that category; a couple in London, a couple in the US, a couple – OK, more than a couple – in France; but there’s an unpleasantly selfish part of me which really, really doesn’t want to share. It’s irrational, and lately I’ve pledged to get the hell over this particular issue, which is good news for you, because you are finally getting to read about places I keep returning to, like L’Atelier de Joel Robuchon and Le Gavroche (the pic is pinched from Wikimedia Commons – I hate bringing a camera to places like this). You’ll also get to read about several of my favourites, so far jealously unshared, in October, when Food Journeys of a Lifetime: 500 Extraordinary Places to Eat Around the Globe is released – it’s a National Geographic publication, and 20 of those extraordinary places were written about by me. More on that when the book finally comes out.

So. Gavroche. You know the chap – grubby urchin in Les Miserables. And you’re probably aware of the food royalty that own and still run the restaurant, founded in 1967 by Michel and Albert Roux. The kitchen is now run by Michel Roux Jr (son of Albert), and both older chefs still take an active interest in the place; good news for chefspotters. (I’m an avid one, and I was as pleased to see Albert Roux walk past my table on Monday as I would have been to see Brad Pitt, who is doubtless much less deft with artichokes.)

As usual, I rolled up for a weekday lunch, part of what I consider the freelancer’s dividend. I’ve mentioned it before, but if you’re in a position to do this, it bears repeating: many of London’s best restaurants offer surprisingly well-priced lunch menus in the week. The weekday set lunch menu here is, at first glance, pricier than elsewhere, at £48 a head – but this sum includes half a bottle of wine (you’re given a choice of four, which are always beautifully selected – ours was a 2004 St-Emilion Grand Cru from Chateau Vieux Sarpe, carefully decanted at the table); half a bottle of Evian; and coffee and petits fours, which most other places will have you pay for separately at lunchtime. The food itself is as good as you’ll find in the UK, and generous amuses bouches and petits fours (who knew that physalis, caramel and coconut was such a good combination?) round things out so well that you’ll leave thrilled at the value of what you’ve eaten.

The amuses are always good – to be honest, they’re often extraordinary. Artichoke Lucullus, cut into elegant crescents and stuffed with summer truffles, foie gras and chicken mousse; sea bass carpaccio; little toasts with a blue cheese mousse so beautifully balanced I could have eaten a dozen more for a main course.

Once you launch onto the menu proper, you’ll find there’s some clever work going on balancing luxe ingredients like truffles and foie gras with delicious things which cost the kitchen far less – a perfectly poached egg balanced on a Russian salad of potatoes, peas, carrots and celeriac sounds good but dull until you realise there are a couple of gargantuan slice of summer truffle perching on top, and a creamy truffle emulsion binding the vegetables together. Girolles are paired with a slow-cooked lamb’s tongue, cut into meltingly tender slices. It’s one of those menus where you’re hard-pressed to make a decision, everything sounding so perfectly edible – I should also point out that it’s one of those menus that’s written entirely in French. I used to live in Paris, and I’m the sort of anal-retentive who takes great pleasure in memorising the French for things like guinea fowl and fairy-ring mushroom. Even so, I came unstuck and had (horror!) to ask for help from the waiting staff. My friend and I were pretty sure Maigre was a sort of fish – but what sort? And what was a Sauce Antiboise? (It’s a white fish related to the sea bass, it turns out; and Antiboise simply means ‘from Antibes’, which I should bloody well have known. It’s a raw tomato concasse with basil and olives…and probably much more, but my dining companion was very sensibly preventing me from eating everything on her plate under the pretext of making notes.)

The staff (to a man/woman, French) are supremely helpful and will offer all the help you need with translation – you are clearly not expected to know what a maigre is, which makes me question the usefulness of the monoglot menu. Two of them are also supremely disconcerting. They’re identical twins, with matching extravagant hair dye, matching statement glasses, and matching mis-matched earrings. Cue a nanosecond of worry that an hallucinogen has been slipped into your Salade Russe.

This is the sort of restaurant where I’m happy to order veal liver. There’s a certain mental accounting you need to do when you next encounter it on a menu. Consider for a moment how much veal you see in British restaurants. There’s very, very little; even saltimbocca is usually made with pork these days. Now consider how much veal liver you see on menus (a surprising amount), and how many livers the average calf has. (That’s one, for those without a Biology GCSE.) There are simply not enough veal calves being eaten in the UK to provide the number of livers you’ll see on menus. The inevitable upshot is that much of the stuff you’ve ordered under the guise of veal liver has actually been beef liver – with the coarser texture, strong odour and flavour that that implies – so I never, ever order veal liver unless I’m somewhere I’m absolutely confident won’t palm me off with a superannuated gland. The liver at Le Gavroche is the real thing, so fresh it gives to the teeth like the flesh of a ripe plum, and its delicate flavour is seasoned sensitively with a very gentle green peppercorn sauce and a shallot confit. Ask for it to be served pink – simply beautiful stuff.

The cheeseboard is simply enormous, stacked high with French bliss, but we had our heads turned by the poached peach with champagne and raspberry mousse. A whole, peeled white peach, stone still in, had been poached to perfect silky softness in champagne, like a solid Bellini, and stood up in a swirl of raspberry mousse, just tart enough to offer a contrast. Regular readers will know that I don’t have much of a sweet tooth, but even I would have turned down a fine bacon sandwich if offered this instead. (This doesn’t sound like much of a compliment. Believe me, it is. I will do almost anything for a fine bacon sandwich – husband, take note.)

Of course, not everything here is perfect, or I would have set up a tent under one of the tables by now. Gavroche, the eponymous urchin, appears thumb-sized and in glorious 3D at the bottom of the shaft of all the cutlery, and frankly, he’s hideous. Like the decor – this restaurant perfectly apes a 1980s gentleman’s club, down to the carpeting, the green leather banquettes and the awful art on the walls. When I was a kid in the 80s, we had a very wealthy hotel-owning, huntin’, shootin’ neighbour, who affected plus-fours and displayed photos of himself with strings of recently murdered trout on his walls. He’d be right at home here with the ugly beaten-metal sculptures

of edible birds, which the restaurant sells for thousands of pounds to…someone. The room, and its clientele, is overwhelmingly masculine – we were the only all-female table in the place. But I don’t care – they welcomed me with a crescent of artichoke full of foie gras, truffles and chicken mousse, so they can be as ugly and male as Rasputin for all I care.